Dive Brief:

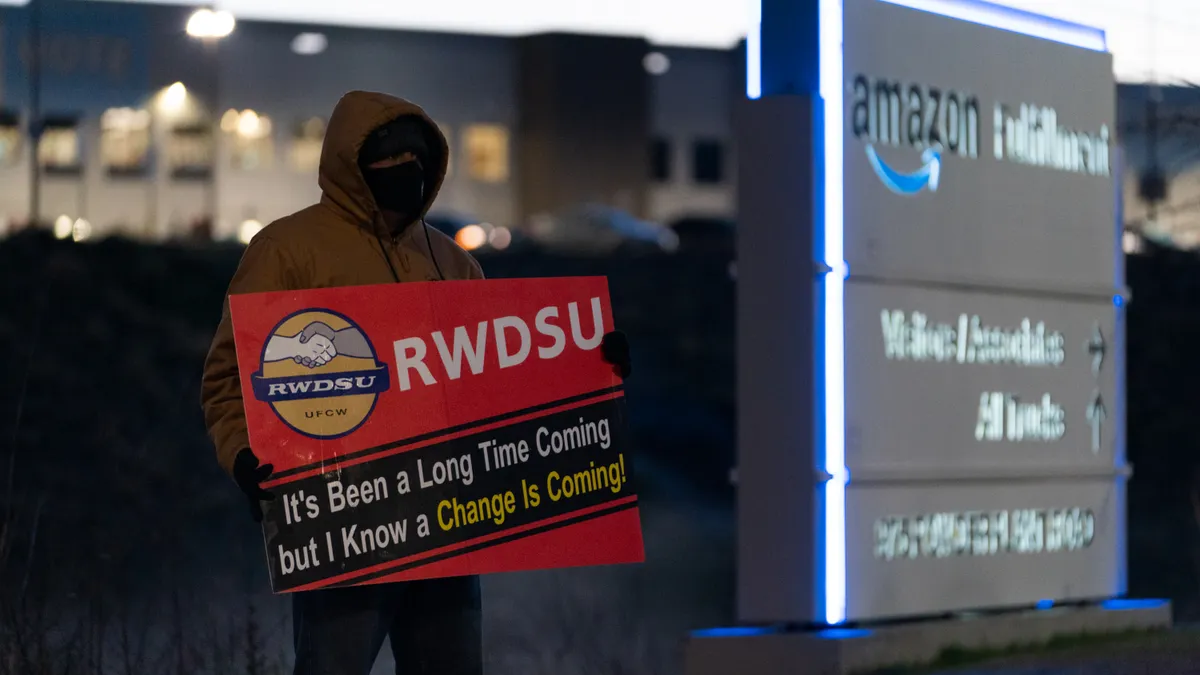

- In a decision released Nov. 29, the National Labor Relations Board ordered a new election in the case of Amazon workers at a Bessemer, Alabama distribution center, some of whom sought to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union this past spring.

- The contentious battle over unionization at the facility drew the nation's attention in the weeks prior to the vote and was far from settled afterward. Although the bid to unionize was rejected by 1,798 workers (compared to 738 workers who voted in favor of unionization and thousands abstaining from the vote), RWDSU filed objections soon after, citing "objectionable conduct" from Amazon. After a review period spanning eight months, the NLRB agreed with several of these objections.

- The first election will be set aside and the manner, date, time and place of the second election will be specified in a forthcoming Notice of Second Election, the NLRB stated.

Dive Insight:

The NLRB's most recent decision marks a win for the union and the workers who organized to join it. It also demonstrates how companies can sabotage their own wishes for nonunionization.

Following the election, RWDSU filed 23 objections, the majority of which were considered in a hearing by the acting regional director of the NLRB. Ultimately, the union and hearing officer withdrew or rejected many of those objections, leaving the decision down to seven objections, six of which were dubbed "the mailbox objections" in the NLRB's decision.

The mailbox objections centered on Amazon's installation of a ballot collection box in the employee parking lot near employer-operated video cameras and beneath a tent that featured a slogan — "Speak for yourself!" — from the employer's own anti-union campaign. According to both the hearing officer and the regional officer of the NLRB, these actions raised several election-related issues, including "solicitation, the collection and security of the mail ballots, surveillance or the impression of surveillance, and the false impression that the Employer — not the Board — controlled the election."

In its responses to charges of misconduct, Amazon argued that the ballot box served a legitimate purpose; that it did not conflict with the pre-election Decision and Direction of Election or established Board election procedures; and that the box could not have affected the election results.

The regional officer disagreed, noting that whether the box served a legitimate purpose was irrelevant, that Amazon "undermined the Board's authority" by independently contacting the postal agency and installing the mailbox "in a manner inconsistent with the pre-election DDE's instructions" and that it had never met with the precedent of a company attempting to install a postal mailbox.

In addition to the mailbox objections, the regional officer found issue with Amazon's small "captive audience" meetings — mandatory meetings at which companies campaign against unionization — due to Amazon's proffering of "Vote No" paraphernalia. Campaign leaders encouraged workers to take the items on their way out of the meeting, leading NLRB to conclude that employees were forced to make an 'open and observable choice' regarding their support for or rejection of the union, which is a matter of improper polling.

The NLRB did not argue or have to show that Amazon tampered with employees' votes or otherwise forced the election in its favor; by creating circumstances that could reasonably stoke fear in employees or mislead them regarding the election's control, Amazon ran afoul of the agency.

While captive audience meetings are allowed by the NLRB — something the Pro Act, which stalled in the Senate earlier this year, seeks to address — employers must be careful to otherwise act in alignment with the National Labor Relations Act and with established precedents issued in previous NLRB decisions.