By almost any formal analysis, menopause — the natural cessation of menstruation that usually occurs between the ages of 45 and 55 — is a subject that very few want to discuss.

In fact, according to a 2022 global survey by market research firm Ipsos, which polled 23,000 adults across 33 countries, menopause ranked below finances, politics and religion on the list of topics respondents said they felt comfortable discussing with friends. While more women in the survey reported being comfortable talking about menopause than men, nearly 1 in 4 women said they were uncomfortable talking about the subject.

But ignoring menopause comes at a cost, not just for those going through it, but also for their employers. Symptoms associated with menopause, such as hot flashes, mood changes, sleep disturbances and cognitive difficulties, add up to $1.8 billion in lost work time each year in the U.S., according to a recent Mayo Clinic study.

Menopause tends to affect the careers and productivity of people who are “very often the most significant contributors to an organization,” said Shelly MacConnell, chief strategy officer at family-building benefits vendor WINFertility. “It is oft-overlooked and only just now becoming a topic of conversation and a topic of action.”

An ‘astonishing’ gap

Yet, when employers are asked about menopause, few appear to understand the extent to which it can affect employees’ lives and color how they perceive their organizations.

In June, Bank of America published a report in partnership with the National Menopause Foundation that found 71% of employee benefit managers said they had a positive perception of their organizations’ culture regarding menopause, compared to 32% of women employees. Only 14% said their employers recognized the need for menopause-specific benefits, even though 51% of peri- and postmenopausal employees said that the condition had negatively affected their work life.

The survey results demonstrated an “astonishing” gap between women and their employers, said Lisa Margeson, managing director, retirement research and insights at Bank of America, in part because employers in the survey predominantly said they did not offer employee benefits specific to menopause because employees had not asked for them.

“Employers are assuming that some of the support services [for menopause] are already covered under their medical plans,” Margeson said, but common treatments such as hormone replacement therapy are often not covered under employer-sponsored health insurance plans.

And when menopausal employees do seek care, they do not always receive necessary treatment from care providers. “There is not a consistency, nationally, in the training that physicians receive in the treatment protocols for menopause,” MacConnell said. “As a result, many people leave feeling unheard and untreated.”

Bank of America’s survey found that health insurance coverage of hormone replacement therapy, access to menopause health professionals, menopause awareness sessions and lifestyle savings accounts with approved use for menopause-related services were among the actions women respondents said they wanted employers to take.

Employers’ support need not be limited to health benefits alone. For example, 10% of women respondents to the Bank of America survey said that employers could provide spaces to cool down.

Similarly, employers should consider how their offices are arranged to ensure access to circulation, such as windows, or air conditioning, said Dr. Lubna Pal, professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive services at Yale School of Medicine and consulting medical director for WINFertility.

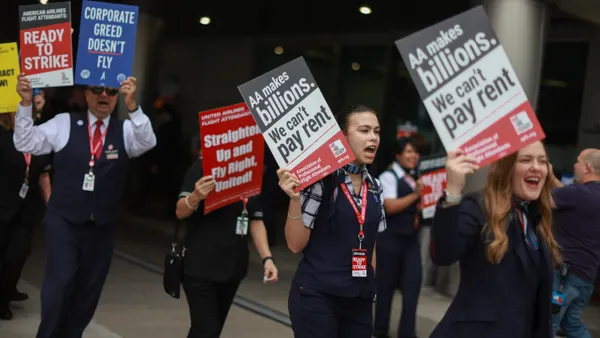

Employers also may want to rethink uniform policies if applicable as certain fabrics and shades can cause discomfort for menopausal employees and may necessitate frequent wardrobe changes during a workday, Pal continued.

Going beyond benefits

Still, in order to truly address the issue, Pal said she believes employers need to think critically about how their workplace culture tolerates and perpetuates stigma about menopause and aging generally. Menopause, she added, represents a phase of life just like any other.

“Every employer needs to take stock of their workforce, and if you have representation in the age group that we are talking about, there are unique needs to consider,” Pal said. “Let's get these conversations going so that employers recognize the need to optimize quality of life for the workforce so that they can do the best they can.”

Discomfort is a challenge employers will need to confront. More than half of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in Bank of America’s survey said they didn’t feel comfortable discussing menopause at work primarily because of the personal nature of the topic. Just under one-third said they feared others perceiving them as old or changes in treatment by peers.

But “without the conversation happening between employers and employees, and without employers asking female employees what they’re looking for or whether they have sufficient support, there’s not open dialogue,” said Margeson, who recommended that HR teams consider whether there are spaces in which employees can discuss menopause at work, such as employee support networks or resource groups.

Crucially, nearly half of women in Bank of America’s survey said they would feel more supported by employers that took such actions.

Managerial training is another avenue to consider, according to Amanda Okill, principal consultant at U.K.-based Byrne Dean. Employers should train managers to be sympathetic and empathetic to those experiencing menopausal symptoms and direct them to available resources. Support from upper leadership is important, too, but employers need to ensure that any leadership statements are backed up by reality on the ground floor.

“No policy or statement from the top is going to make the impact that you want if the reality on the ground is not a respectful workplace environment,” Okill said. “People will not speak out and they will not take that messaging seriously.”