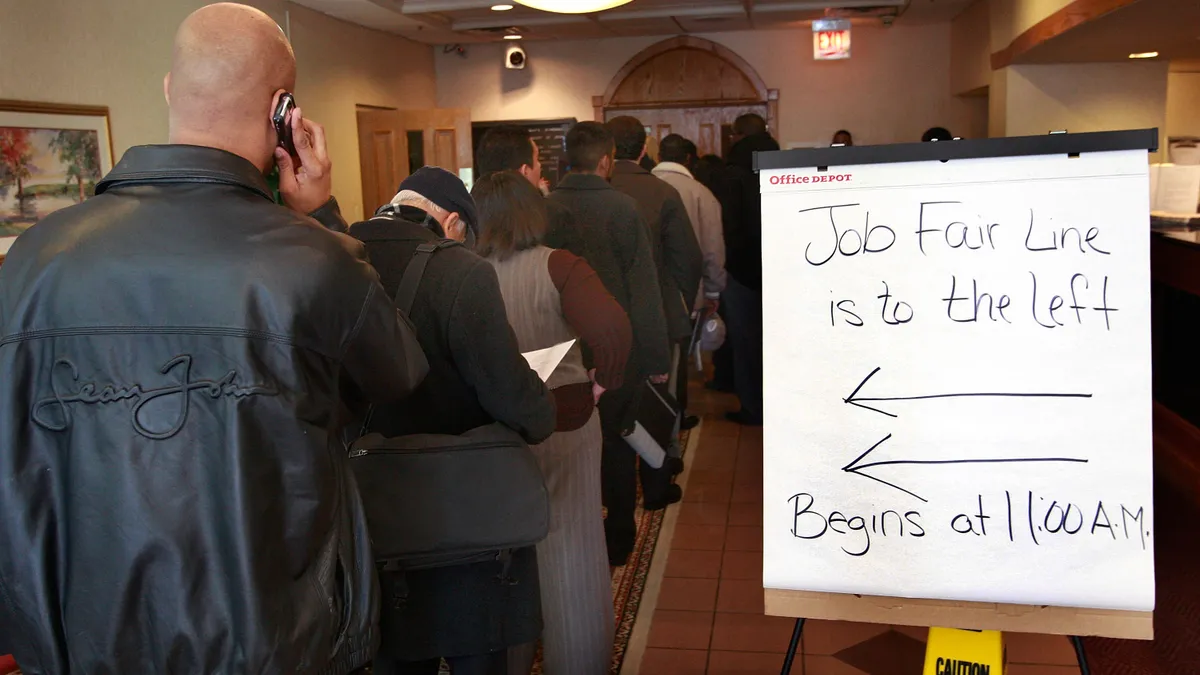

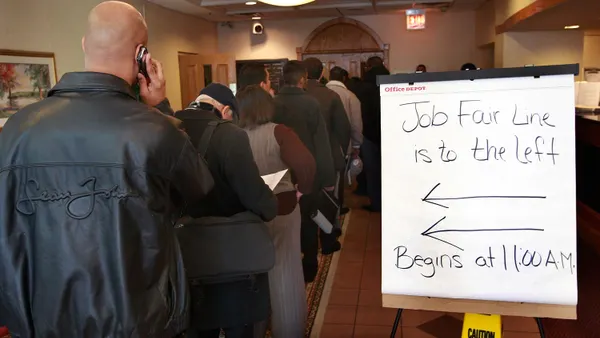

There's no shortage of problems and anxieties encountered by employees in the course of the day-to-day. Irrelevance in the job market has become one of them.

The dynamic and rapid growth of automation in several industries now permeates conversations in the business world; it’s a giant elephant in the room looming over discussions about growth and innovation. Workers, from truckers to fast food cashiers to accountants, are understandably anxious that they’ll be left behind.

Yet, evidence seems to suggest those fears are slightly misguided. Naysayers are quick to point out that robots have quite a distance to cover before they’re able to replace humans entirely, if ever. Businesses employing a large amount of low-paid employees are reinventing some occupations. For HR professionals themselves, there is reassuring evidence that certain aspects of the job are much too human-facing to be delegated to a chatbot.

More tangible than massive occupational disruption, however, is the skills gap. Recruiters in just about every industry know the gap’s effects and have plans in place to combat it, banking on office perks and compensation to lure in-demand prospective workers. But what happens when the well runs dry?

The state of skills

In its 2016 The State of American Jobs report, Pew Research Center found that, among other things, more than a third (35%) of U.S. adults in the labor force said they do not have the right skills and/or education to “get ahead at work.” Concurrently, 54% said that training and new skill development would be essential throughout their career.

These findings connect with trends in job growth; a report from Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW) cited research showing that 73% of all job growth since 1989 occurred within high-skill occupations (including management, healthcare and education). The same report showed “an equally clear shift” away from “production industries” including manufacturing, construction and natural resources which, CEW notes, employ "a large number of workers with lower average levels of educational attainment."

In short, there’s a clear indication in research that workers recognize a need for training and many are convinced they aren’t equipped with the right skills. Meanwhile, the U.S. labor market weighs increasingly toward high-skill occupations. How did this happen?

According to experts who spoke with HR Dive, automation is one of the most significant factors. Holly Benson, VP of organizational transformation practice at Infosys, believes employers would do well to recognize the full extent of the impact automation has on the workforce.

“The skills picture is changing as a result, I think, of the disruption that's happening in business,” Benson said in an interview. “The particular under that is what's happening with the wave of automation. It is pervasive. It is going to be very large. I think it is going to create a significant personnel displacement across different industries.”

Why apprenticeships, and why now?

Long story short, organizations, in recognizing the realities of the job market, aren't just looking for external candidates to crop up for key positions. Increasingly, they're looking to develop talent internally.

Enter the apprenticeship, a form of training that allows workers to "earn as they learn," usually (but not always) with the promise of a full-time position at the end of the term.

Mind you, this concept isn't new to employers, but it is enjoying something of a moment thanks to the skills gap. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that more than 91,000 people entered apprenticeships administered by or registered with the federal government in FY 2016, the most of any year dating back to 2008.

"We're calling [it] the 'x factor.' This idea that there is a real, high correlation to this sense of passion for the job, drive for continuous learning improvement and their ability to make a step change successfully throughout an apprenticeship without the typical background."

Erin Earle

VP of HR Business Partner R&D, LinkedIn

Matt Steinberg, an employment lawyer and partner at Akerman LLP, thinks the reason behind that popularity is partially due to the fear of automation. But the mismatch between postsecondary degree programs and in-demand skills may be a secondary aspect, he said.

"I believe college is a very important thing for people ... but for some components of the workforce, maybe it's not the most important thing," Steinberg said. "There's a huge segment of the population that can benefit from more hands-on apprenticeships than needing to go get an expensive degree which may not necessarily be related to that field."

It's a measure of supply and demand, in other words. But apprenticeships also allow employers to draw from population groups that are traditionally at a disadvantage. Programs like LinkedIn's new REACH program are an example of this idea.

In an interview, LinkedIn VP, HR business partner R&D Erin Earle talked about the the program's aim to draw from a diverse pool of applicants. REACH, which focuses specifically on those interested in software engineering, originally took shape after the company noticed an interesting quality — an "x factor," Earle called it — among participants in Coalition for Queens (C4Q), a New York-based non-profit with which LinkedIn partners.

"Half [of the C4Q] class had college degrees, and half of the class did not." Earle said. "They were finding that they were seeing equal success with their apprentices based on some of this, what we're calling, the 'x factor.' This idea that there is a real high correlation to this sense of passion for the job, drive for continuous learning improvement and their ability to make a step change successfully throughout an apprenticeship without the typical background."

LinkedIn brass saw the opportunity as a way to tap into a segment of the talent market that might have otherwise been overlooked, Earle added, particularly at a time when the company determined it would not be able to hire software engineers at a fast enough rate.

This matches up with an observation made by Benson, who also sits on the World Economic Forum's Council of Gender, Education and Work. Members of the council hear about examples of educational projects in developing nations, and one in particular caught Benson's attention.

"There's a very interesting example coming out of Africa, where certain agencies and partnerships with government had gone into villages in Africa and they were teaching women to code," she said. That lead to her to question some of the assumptions employers typically make about talent development.

"We tend to get ourselves hung up in the Western world about degrees, but there's a whole different model out there," Benson continued. "Can we rethink our basic approaches to this?"

Incentives and compensation

The true test of any training strategy is whether it can successfully engage learners. Companies have attempted this in various ways, but one of the more intriguing is the use of games.

Benson argued that often, employers don't consider what incentives a learner has to complete a given training task or reskilling initiative. In her time at Infosys, she's witnessed the success of gamification first hand.

"All humans like to play games," Benson said, "and the big premise of gamification is that you can use it as both a training and an incentive tool to encourage people to take certain actions." One example of such a training module: a bicycle trip around the world, in which players earned points and could see their day-to-day stats to track their progress.

On the legal front, apprenticeships in particular are a compliance concern when it comes to wage and hour laws, including overtime rules.

"Unless there's any change to the wage/hour laws, you have to treat apprentices as being subject to the wage and hour laws to the same degree as interns," Steinberg said. "I think companies have to be extremely cognizant that just because you call someone an apprentice, doesn't mean you're going to have a defense to a wage and hour claim."

Employers can't go it alone

"For that concept to work, I think it will need buy-in from Congress and beyond in order to protect employers who may, right or wrong, have some concerns about paying an apprentice, because an apprentice may not necessarily have the skill set at that point," Steinberg said. "But the hope is as a society we can kind of coalesce around this concept so that well-intentioned employers can bring people into apprenticeship programs and understand the rules around doing so."

Benson says the topic of reskilling is a major one among members of the World Economic Forum, and that smaller employers — those who likely won't be able to afford expenditures on comprehensive training programs — may need to look to industry partnerships in order to succeed. That's not unprecedented among U.S. firms.

But the focus, it seems, should be placed on the workers themselves. Apprenticeships, after all, are about arming workers with the skills necessary to succeed, especially in an economy that changes faster than they may be able to comprehend.

"For some of these individuals, it's been life changing," Earle said of LinkedIn REACH program participants. "This creates the opportunity for them to have serious project work, developing their coding skills ... but more importantly, [have] that life experience."