Mentorship, discussions of lived experience, programming that fosters a sense of belonging: these are all crucial aspects of workplace diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, according to research and experts in the field.

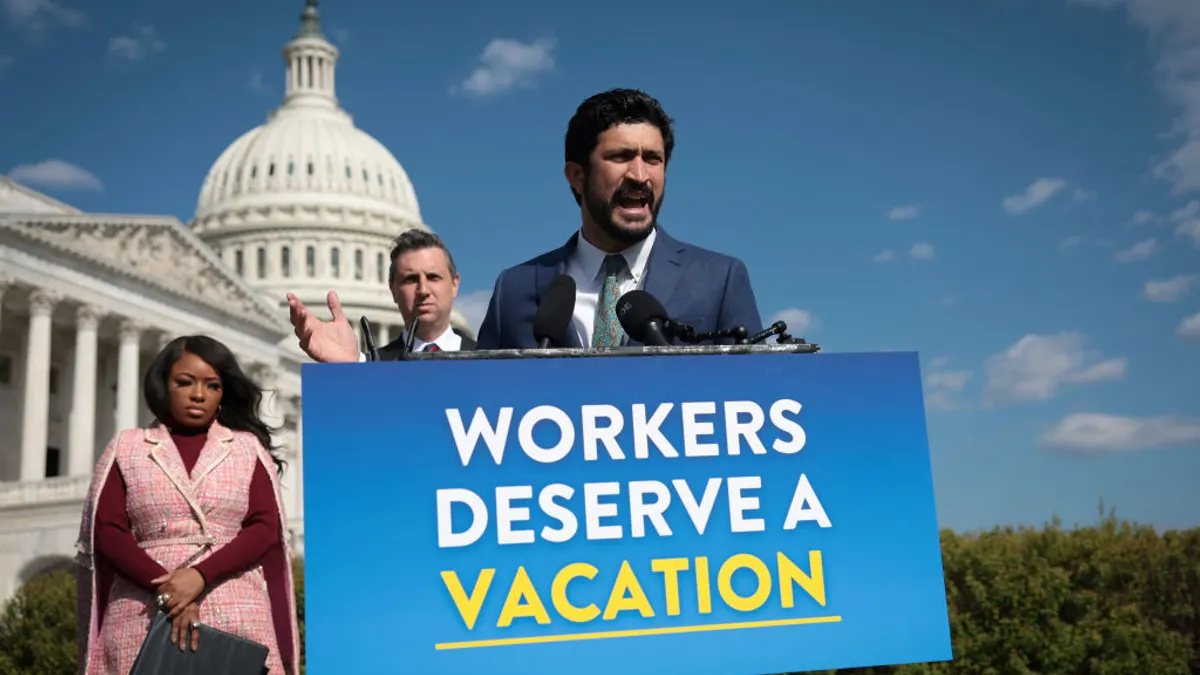

Often, this happens through employee resource groups or business resource groups — which the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and U.S. Department of Justice cited as potentially illegal in guiding documents published March 19. As DEI initiatives face increased scrutiny, the power of affinity groups remains irreplaceable, sources told HR Dive.

One case study exists in Rewriting the Code, a non-profit that provides mentorship and networking opportunities to early-in-career women in tech.

For Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, HR Dive spoke to two Asian American women who belong to Rewriting the Code about the distinct challenges they face in a male-dominated field — and what HR can do to champion Asian American women at work.

The challenge of speaking up

Rejoice Hu, a machine learning engineer at Morgan Stanley, said due to her upbringing, her main challenge is speaking up — “just putting myself out there, and being bold and a lot more vocal about my thoughts.”

Business researchers have long highlighted the challenges associated with women speaking up at work. Previously, SHRM Inclusion included programming on the particular challenges women face in the workplace. Likewise, some women executives are taking note of how terms like “rockstar” or “aggressive” are dog whistles tailored to men in business, especially when assertive women face the brunt of double standards.

The intersection of gender and race comes can come with new challenges. HR professionals have highlighted how the idea of “respect,” particular to the Asian diaspora, can complicate the directive to “speak up” at work.

Being vocal at work as a woman may be even harder for woman of color: In her culture, Hu said the idea is that “your hard work should speak for itself.”

“I think Asians like to keep it humble. It feels very weird when I'm trying to brag — or not even brag, but in this case, vocalize the contributions or the achievements I'm making in the workplace,” she said. “In American culture, the people who get rewarded are the people who are very vocal about their work.”

As a result, Hu has had to teach herself the art of “being OK with taking up space and being loud.”

HR professionals and managers looking to help Asian workers take up space can potentially encourage workers to log their big accomplishments: “What really helped me is keeping a document or tracker that outlines all of my wins and achievements. I like to send weekly or bi-weekly updates to my manager to make sure, if I do have trouble speaking up or vocalizing about what I've accomplished so far, that I have it all in writing,” Hu said.

She added that this approach to sharing her wins gives her time to think about how she brings value to the team each day, and how she wants to present her accomplishments to her manager.

The Asian diaspora is not a monolith

Hua Szu Yang, a software engineer at Uplight, also said her challenge has been “learning to adapt to different workplace norms,” but that looks different from Hu. Yang said that how she spoke with her family and community growing up was more direct.

“Passive-aggressive communication is not uncommon in the workplace, at least in American companies that I've worked at,” she said, adding that this “additional cognitive overload” has created a learning curve for her.

Yang emphasized the importance of individuality when discussing Asian talent. Acknowledging that the Asian community is not a monolith “would probably increase feelings of belonging and acceptance,” she said.

Part of this means not just sending an email saying “Happy AAPI Heritage Month.”

“It checks the box of, ‘Sure, you should say that,’” Yang said, but it's not the same as acknowledging what’s “within ‘AA,’ within ‘PI.’”

“There are so many different backgrounds and traditions and cultures that encompasses, and usually we can't tell based on surface level understanding of someone what their unique stories might be,” Yang said. In short, HR has an opportunity to go “deeper.”

In her own life, Yang recalled how when she was in college, she found that even other first-generation, Asian college students had different lived experiences than her. “I came from an urban background,” she said. “I met people from not urban places at all — people from rural places. We shared the commonality of ‘the first in their family to go to college,’ but we came from very different backgrounds.”

A recurring theme Yang found was that her peers’ families didn't encourage them to attend college because they wanted their kids to work on the family farm. Her classmates were told, “College is not for people like us.”

“When we dig into unique stories, we can see the unexpected commonalities, but also the unexpected differences that make life so much richer,” Yang said.

In the face of challenges: The power of belonging

For the most recent Women in the Workplace report from McKinsey & Co., researchers wrote that “the workplace has not gotten much better for women. Women today are no more optimistic than in the past about their gender’s impact on career advancement, even as they remain highly ambitious—and just as ambitious as men.” That report also highlights that Black, Latina and Asian women are still likely to perceive their race as an obstacle to advancement.

Notably, in a 2022 study on the workplace experiences of women of color in tech, Asian women reported having to do office housework and workplace emotional labor at high levels. Joan Williams, professor at the University of California, Hastings School of the Law and co-author of the study, has spoken at length about how Asian American women face the brunt of microaggressions and workplace harassment in tech, according to her research.

Regarding Asian American women in particular, Kristin Austin, VP of culture and community impact at Rewriting the Code, told HR Dive via email, “Spaces like RTC remind them they were never ‘too quiet,’ they were simply surrounded by people who didn’t listen loud enough.”

Yang, who has been active in Women Who Code and a women-in-business group when she attended Harvard University, said, “It feels empowering to be part of our group where we can all share, we have some shared experience of what it's like to be a woman in the workplace. And at the same time, there's a lot of diversity within that.”

For Hu, discrimination against women in tech was top of mind for her, from day one. Apart from doing research on the issue, she even found this to be true anecdotally in her freshman year computer science class: “I did notice that a lot of my classes were mostly male.”

This prompted Hu to check out several women in tech groups, including Women in Computing at Cornell University. “The sense of community that I felt from it was really, really strong,” she said.

“Coming in as someone who had zero knowledge about how this industry worked — internships in general, what kind of classes to take, how to crack the whole recruitment process — I was super, super lost. Rewriting the Code provided me with that opportunity, that community and all those resources,” she explained.

Hu said she gained even more than just access to networking opportunities. She recalled second-guessing herself, having been focused on biomedical engineering and asking herself, “Should I join tech or not?”

Whether an employer sticks with DEI or ultimately axes their program, there may be benefits to HR encouraging workers to seek affinity groups outside the company. Now that she lives in New York City, Hu has joined the early career group and is able to bond over tech-specific workplace struggles, such as rounds of industry layoffs.

“I think that's been really, really valuable,” Hu said.