Editor’s note: Katie Clarey is a regular freelancer with HR Dive. Her column, Back to Basics, began four years ago, when she started covering employment law. If you’re new to HR (or just need a little refresher), follow along as she speaks with legal experts, peruses federal guidance and lays out the basics of federal employment law. Feel free to send tips, questions and feedback to [email protected].

In a recent Back to Basics column, I asked you to imagine you were a recruiter who had just caught wind of a no-poach agreement struck by some of your competitors. I want you to become that recruiter again today.

When I left you, you were replaying the conversation you just had with a rival recruiter at a job fair. The recruiter let it slip that her company signed a no-poach agreement with a fellow competitor. She wondered if you’d be interested in doing the same. Your instincts told you to dodge the question, and your instincts were right: The U.S. Department of Justice is keenly focused on antitrust enforcement right now.

Staying far, far away from this no-poach agreement is a good way to make sure you don’t have to face DOJ’s wrath. But it irks you that your competitors are using illegal tactics to manipulate the market. You’re hurting for talent, too, and agreements like theirs only make the market worse. What can you do?

This situation illustrates employers’ somewhat unique relationship to the Justice Department. Normally, employers dread government action. But when they experience criminal conduct as a “victim” or want to avoid liability, “there are opportunities for companies to work proactively with law enforcement authorities,” according to Edward J. Loya, Jr., member of the firm at Epstein Becker Green.

“Employers are not always on the defensive when it comes to government action,” he told me in a recent interview. “Sometimes, companies want to know about the white-collar criminal statutes DOJ enforces so that they can work proactively with law enforcement when they are harmed by an employee, a competitor, or some other bad actor, and the facts and circumstances warrant it.”

‘A large government law firm’

The DOJ dates back to the early days of the U.S. The agency’s first attorney general, Edmund Jennings Randolph, was appointed by President George Washington in 1789. These days, the department employs more than 115,000 people to maintain its mission: “to uphold the rule of law, to keep our country safe and to protect civil rights.”

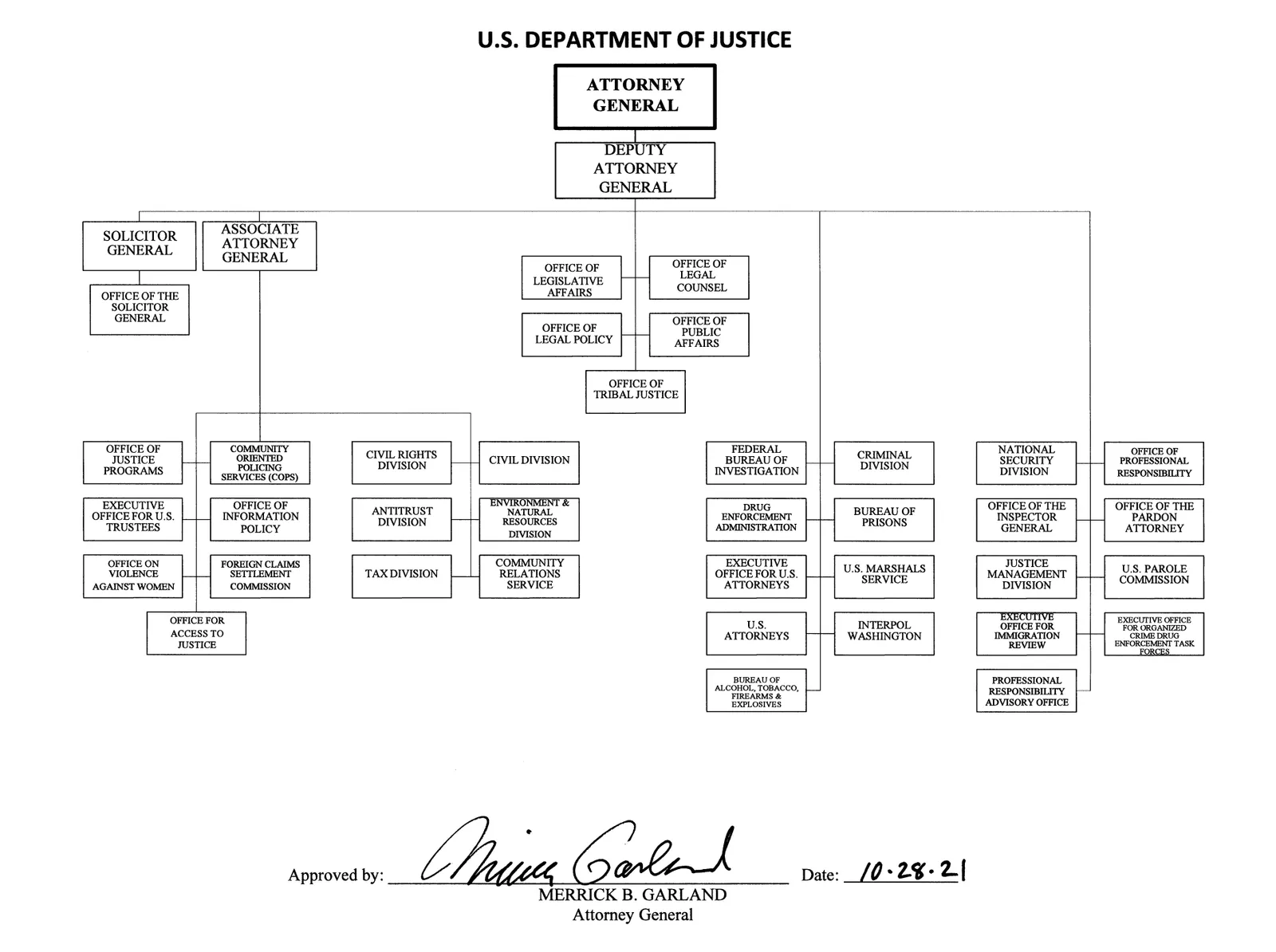

Loya, who worked in DOJ’s criminal division between 2008 and 2013, describes the agency as “a large government law firm.” It comprises many different divisions and components, each with its own specialty.

“Most focus on enforcement or defensive litigation, but some are deliberative in the sense that they provide legal advice to federal agencies or offices,” Loya said.

DOJ’s basic purpose, Loya said, is to enforce federal criminal laws. DOJ is headquartered at Main Justice in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Attorneys’ Offices operate essentially as DOJ’s “field offices,” which are based in different federal districts throughout the country. These offices have jurisdictions within their districts, and DOJ can send its prosecutors across the country, as long as they are working within their sections.

Increased scrutiny

Unlike the U.S. Department of Labor or the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, DOJ enforces no statutes that are employee-specific. But there are statutes that employees are in the best position to violate, Loya said. This perspective, however, is somewhat new.

“Experts haven’t really been looking at recent white-collar federal criminal law enforcement trends from the perspective of focusing on crimes committed by employees, or company insiders, in the workplace. But the latest cases coming out of DOJ — and the DOJ’s new enforcement priorities — show that there is now a significant overlap between workforce issues and white-collar crime,” Loya said.

Employers typically consider DOJ’s regulations and statutes according to their industries. From a general perspective, employers should be aware of several universal statutes, Loya said. This awareness not only helps companies stay out of trouble — it also prepares them to confront illegal activity. Employers want to know such laws so they can refer potential criminal violations to DOJ from two sources: Third-party bad actors (like competitors) and their own employees.

“In many instances, these matters involve ‘rogue’ employees — that is, employees engaged in potential criminal conduct about which the employer has no awareness or involvement,” Loya said. An employee may steal trade secrets from a competitor and use those trade secrets to benefit her employer. Or an employee may say yes to an invitation to a no-poach agreement.

Employers are likely familiar with statutes banning fraud and embezzlement. The statutes below comprise a growing body of criminal law being used to increase scrutiny on companies and employees, Loya said.

- Employee self-dealing: Several statutes ban forms of kickbacks and self-dealing in which company employees are involved. The Travel Act incorporates state commercial bribery laws as predicate offenses, Loya said. The “Honest Services” fraud statute can be applied to private sector employees. And the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act prohibits, among other things, employees acting on a company’s behalf from bribing foreign officials to benefit their business interests.

- Trade secrets theft: The Economic Espionage Act of 1996 targets the theft of trade secrets. This statute prohibits someone from stealing or misappropriating a trade secret to the economic benefit of anyone other than the owner, Loya said. In many cases, a company’s competitor or someone acting on the competitor’s behalf is involved in theft of trade secrets. When an employer learns of that happening, it will need to evaluate whether it makes sense to refer the matter for criminal investigation.

- Unfair advantages: The Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits price fixing and monopolization and specifically bars employers from striking no-poach and wage-fixing agreements. This area is of particular importance to employers and HR pros, given the DOJ’s recent focus. And yet, as much as the antitrust division is trying to prosecute this issue, it hasn’t secured any trial victories, Loya pointed out. Still, another attorney, Proskauer Senior Counsel David Munkittrick, told me that employers can expect more attempts at enforcement. “Despite some initial losses in its no poach enforcement efforts, the DOJ has only doubled down, and we can expect more to come,” Munkittrick said.

Interacting with DOJ

When employers notice activity that violates these statutes, they can contact DOJ.

“DOJ investigations are normally disruptive and distracting to businesses. But in more cases than one might expect, employers have an interest in making sure DOJ does a good job enforcing federal law,” Loya said. “We have fair and more efficient competition between competitors, better workforces, and stronger consumer protection when the rule of law is enforced and there’s a fair playing field among competitors.”

When an organization refers a case for criminal prosecution, it typically hires outside counsel, Loya said. Counsel may reach out directly to the agency, to the U.S. Attorney’s Office or to the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The criminal referral process typically involves three main steps, according to Loya:

- Identifying a government official to receive the criminal referral.

- Preparing a written criminal referral that summarizes the potential targets of an investigation, the alleged criminal violations, the factual allegations, and relevant documents and/or witnesses who may have helpful information to the government.

- Participating in follow-up discussions with the government about the criminal referral.

“Because a company that refers a case for criminal prosecution is normally situated as a ‘victim’ in the case, the government will expect the company to cooperate in the investigation if the government agrees to open a case,” Loya said. “Typically, after the government agrees to open a case, it will issue a grand jury subpoena to the company for documents so that the government can be sure that, among other things, it has received all the relevant information from the company.”

When employers are on the other end of a case — when they’re acting on the defensive — the government will send a grand jury subpoena or contact the company to set up times to interview employees. Experienced counsel will help employers navigate investigations out of the DOJ or the U.S. Attorneys’ Offices. Once a company determines whether it is a “subject, target or fact witness” in an investigation, Loya said, it can prepare a strategy with counsel for moving forward.