Dive Brief:

- A class of current and former Target warehouse workers at distribution centers in New Jersey agreed to accept $4.6 million to settle state law claims they weren’t paid for walking long distances to and from their stations to undergo mandatory pre- and post-shift security screenings, according to their Oct. 24 court motion.

- Per the complaint in Sadler v. Target Corp., the named plaintiff was an hourly nonexempt employee at a warehouse in Bridgeport, one of three Target distribution centers in New Jersey that collectively span more than 2 million square feet. She alleged that before warehouse workers can clock in, they have to show their ID at the facility entrance, undergo mandatory pre-shift screenings and walk long distances to their work location. At the end of their shift, they clock out and take the lengthy walk back to be screened again before they can leave, the complaint said.

- According to the lawsuit, Target allegedly violated the New Jersey Wage and Hour Law by failing to count this pre- and post-shift walking time as “hours worked,” causing the warehouse workers to be deprived of minimum wage and/or pay at the proper overtime rate. Target denied the allegations, particularly that the walking time was compensable, the complaint said. In June, the parties agreed to the settlement, which must now be approved by the court.

Dive Insight:

Target is fighting similar claims in New York, according to a class-action lawsuit filed in August.

The New York plaintiffs alleged that hourly workers at Target warehouses in Wilton and Amsterdam can’t clock in until after they enter the facility, swipe their employee badges for security purposes, and walk up to half a mile to their assigned departments. At the end of their shifts, they’re required to clock out before walking back to the entrance to swipe out.

One plaintiff alleged that when she worked as a packer, it took her 8-10 minutes to walk from the entrance to her work area. Another plaintiff said it took him 5-6 minutes. They alleged Target failed to pay them for this time, and in doing so, failed to pay them at their promised wage rate and failed to pay them state minimum wage for all hours worked, in violation of the New York Labor Law.

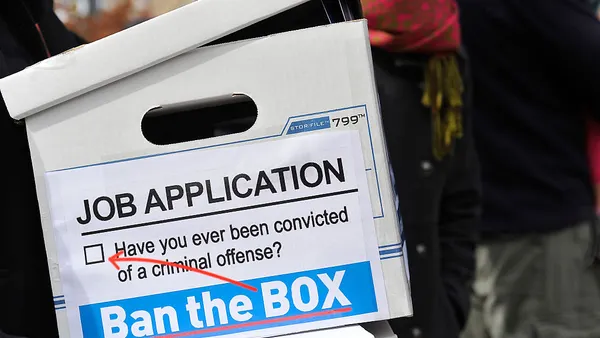

The cases turn on a commonly contested issue: When do hourly employees have to be compensated for pre- and post-shift activities?

In a seminal ruling in 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court laid out the standard for lawsuits brought under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The justices held that a staffing company did not have to compensate warehouse workers for the time they spent after their shift waiting in line to undergo security screenings because the screenings were not their principal activity, or not “integral” or “indispensible” to it.

However, a U.S. Department of Labor guidance points out that some states may provide more protection than the FLSA, including a higher minimum wage, and when they do, employers must comply with both the FLSA and state law.

A 2022 settlement reminds employers that under state law, the outcomes may be very different. In the case, which asserted violations of California law, a court approved a $30.4 million settlement agreement between Apple and a class of workers required to undergo off-the-clock bag searches.

Prior to the settlement, the California Supreme Court found that under California law, time spent waiting for and undergoing bag searches is compensable as “hours worked” because the employees are still under Apple’s control.

Target argued in an Oct. 27 motion to dismiss that the New York plaintiffs don’t have a claim because New York law and its corresponding regulations incorporate the FLSA, which doesn’t include as “hours worked” preliminary and postliminary activities, such as “walking … to and from the actual performance of the principal activity.”

In contrast, the New Jersey lawsuit asserted that Target warehouse workers there are entitled to be compensated for the walking time because under New Jersey law, “hours worked” includes “all time that employers require their employees to ‘be at his or her place of work.’”