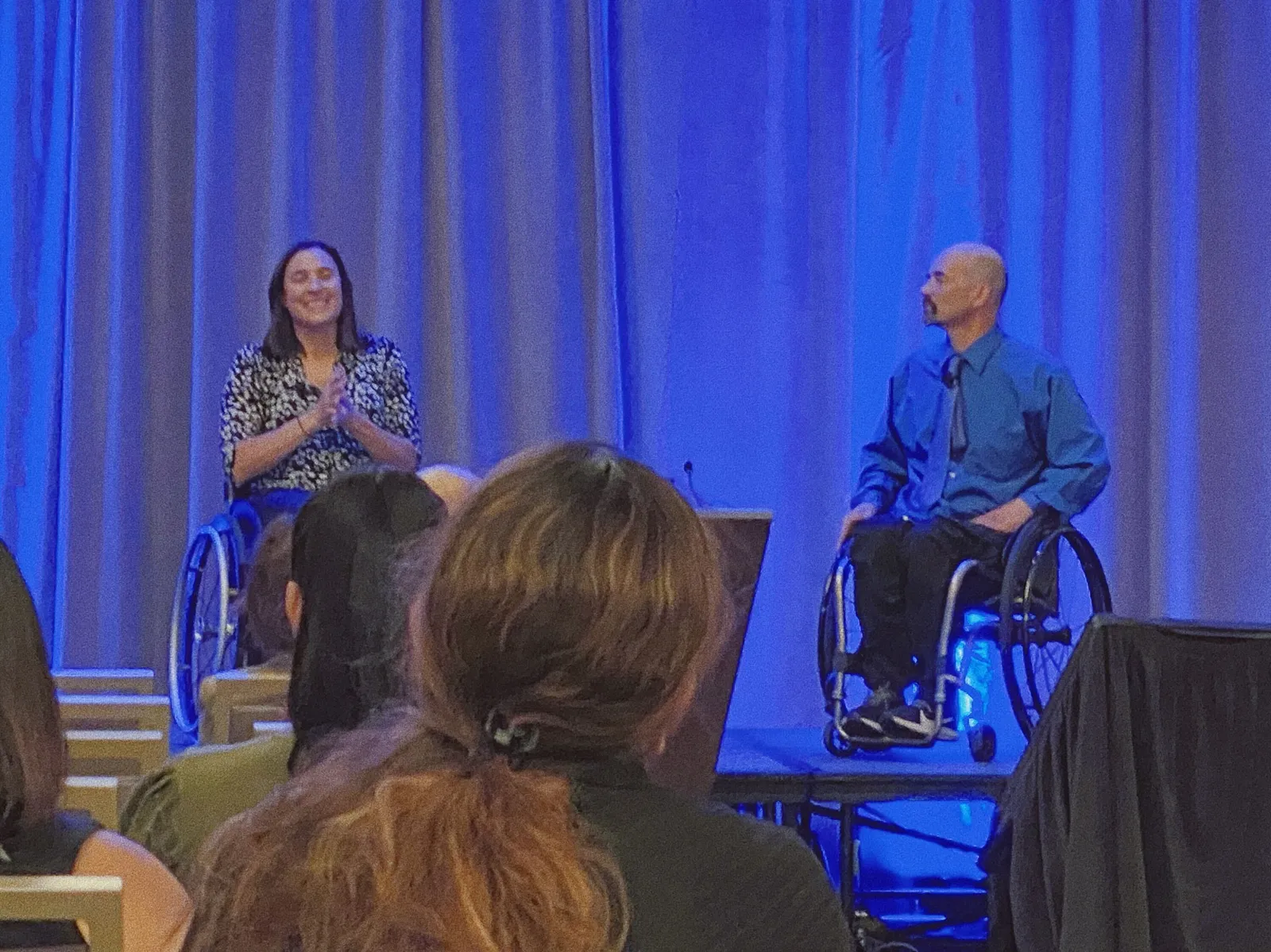

Tricia Downing and Erik Kondo — two speakers at this week’s SHRM Inclusion conference — are not inspiration porn.

The term is used by many disability rights advocates — notably, the late Stella Young in her 2014 TEDx Talk — to describe the patronizing ways disabled people are used as symbols of resilience and exceptionalism, regardless of whether that praise is warranted.

The speakers opened their session by observing that stories about kids with disabilities scoring “incredible” touchdowns — in middle school, on high school teams and among college athletes — continue to go viral. Likewise, prom-posals including this demographic are billed as extra heartwarming.

They also offered their own experiences: Kondo recalled a non-disabled runner coming up to him post-5K, saying that the mere sight of Kondo wheeling along compelled him to finish the race. And Downing simply picked up some spinach in the produce aisle, and a fellow shopper caught sight of her and lauded her as “so inspirational.”

The main takeaway from the session was that people with disabilities just want to be themselves, at work and at home, free of the condescending or limiting gazes of people without disabilities.

In her TEDx talk, Young shared similar stories. Her parents declined an offer to nominate their 15-year-old daughter for a community achievement because, as she put it, she hadn’t done anything beyond get good grades and keep up with “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” She recalled a student interrupting her legal studies lecture to ask her when she was going to give “the talk” that he had witnessed all adults in wheelchairs, up until that point, give to galvanize youth.

“That’s when it dawned on me: this kid had only ever experienced disabled people as objects of inspiration,” Young told her crowd in Sydney. She understood because, she said, “for lots of us, disabled people are not our teachers, our doctors or our manicurists. We’re not real people. We are there to inspire.”

In the SHRM session, it was apparent that one attendee had realized in real-time, during Downing and Kondo’s talk, that maybe the aforementioned touchdown videos were offensive. The conference-goer confessed that she had shed tears watching the video — not because of the boy’s disability, she clarified, but because of his energy.

The speakers reinforced this litmus test: Ask oneself, “Would I have the same reaction if this person was not disabled?”

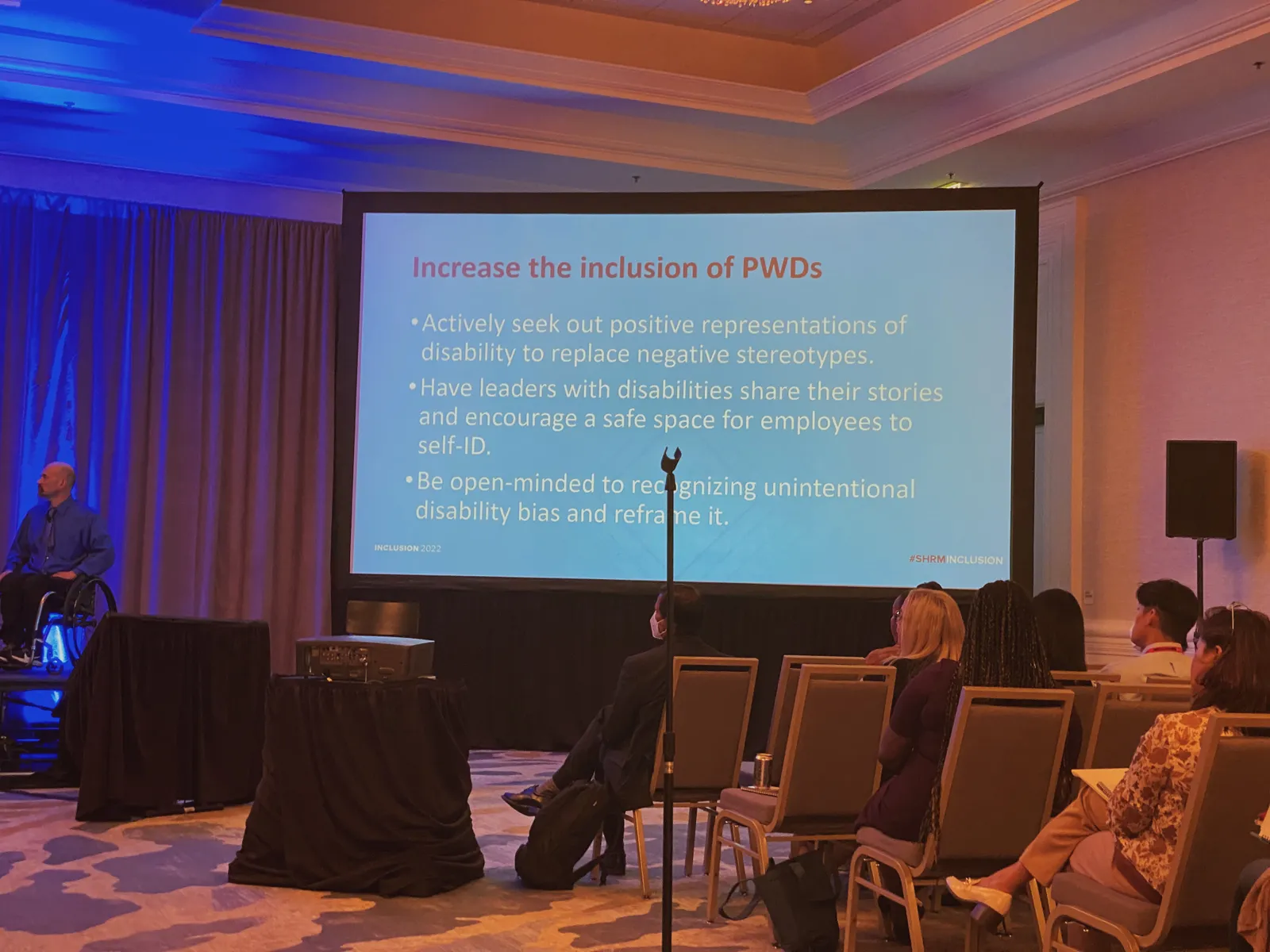

Access to career development opportunities and job accommodations are important; however, disability inclusion at work goes so much farther than compliance. Microaggressions need to be addressed, speakers insisted. Moreover, employers and HR pros should focus on creating workplace safety for people with disabilities, beyond ADA accessibility, they said.

Downing acknowledged to HR Dive that developing a strategy around psychological safety for workers with disabilities is difficult. “I don't think there's an easy answer,” she said. But creating space for company leaders to discuss their disabilities is a start.

“During COVID, we've all become more transparent, right? I mean, we've looked into our co-workers’ homes. We’ve their kids; we've seen their dogs. Hopefully, we can start treating people as humans,” she said, adding that every human encounters the gamut of life experiences.

Her bad day is the same as that of a non-disabled person, she emphasized. “Sometimes, they might have a headache. When I have a headache, then all of a sudden, it's like, ‘Well, she has a headache because of her disability,’” she shared. “That's why we have to get to that place where we're seeing people with disabilities as people, not as their disability.”

Beyond learning from other business leaders, HR professionals can consider the different approaches to disability advocacy: the medical model versus the social model.

The SHRM speakers explained that under the medical model — also known as the charity model, reflecting the rise of 1970s charity telethons – disabilities are seen as “defects.” People with disabilities are “broken” and ought to be “fixed.” They are to be pitied and, from the SHRM speakers’ experiences, their opinions and experiences are non-factors.

In turn, the social model posits that people are only “disabled” because of the barriers upheld by society — disability is more a matter of poor design. “Barriers can be anything from digital — we’re talking a lot about websites, these days — from physical to attitudinal,” Downing emphasized to the SHRM Inclusion audience.

Mindset shift remained a theme throughout the session, reminiscent of what Young said at the end of her 2014 TEDx talk: “Disability doesn’t make you exceptional — but questioning what you think you know about it does.”